The Blood Wolf eclipse is occurring in outer space as I start here, sleepless.

Lately, I've been attempting an essay about cremation, about fires. I've had fits and false starts since September when I heard on the radio in real time that the National History Museum in Brazil was on fire; many of its collections would be reduced to char and ash: a million rare butterfly specimens shriveling in the heat, their iridescent wings exploding like stars. I felt wordless and still. A storehouse of memory, lobotomized.

I have a particular cabinet of curiosities formed from this one fire, fires that continually burn in my thoughts:

The Hartford Circus fire of 1944.

The 1893 fire at the Chicago World's Fair.

The burning of the Natural History Museum in Brazil.

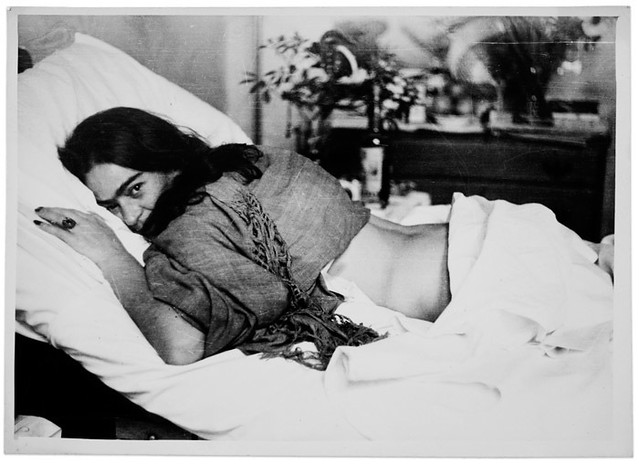

Frida Kahlo's cremation:

"Incinerated, she sits bolt upright in the oven, her hair on fire like a halo.

She smiles at her friends before dissolving"*

Thinking of bodily fires, I remember reading about the Japanese death practice of Kotsuage: when family members sift through the cremated ashes of their loved ones for bone fragments with chopsticks, gathering them in an urn in bodily order, foot bone fragments first, and upwards, so their beloved is not turned upside down in death.

This collecting reminds me of Percy Shelley's funeral pyre on the shores of where he drowned. His heart ( possibly due to calcification from tuberculosis ) resisted burning and was snatched from the flames. Mary Shelley kept it wrapped in his poem 'Adonais' within her desk until 1889 when it was buried in the family vault.

There are connections here, a constellation of grief.

On Shelley's gravestone:

lines from Ariel’s Song, via Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”:

“Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

* via Hayden Herrera

Lately, I've been attempting an essay about cremation, about fires. I've had fits and false starts since September when I heard on the radio in real time that the National History Museum in Brazil was on fire; many of its collections would be reduced to char and ash: a million rare butterfly specimens shriveling in the heat, their iridescent wings exploding like stars. I felt wordless and still. A storehouse of memory, lobotomized.

I have a particular cabinet of curiosities formed from this one fire, fires that continually burn in my thoughts:

The Hartford Circus fire of 1944.

The 1893 fire at the Chicago World's Fair.

The burning of the Natural History Museum in Brazil.

Frida Kahlo's cremation:

"Incinerated, she sits bolt upright in the oven, her hair on fire like a halo.

She smiles at her friends before dissolving"*

Thinking of bodily fires, I remember reading about the Japanese death practice of Kotsuage: when family members sift through the cremated ashes of their loved ones for bone fragments with chopsticks, gathering them in an urn in bodily order, foot bone fragments first, and upwards, so their beloved is not turned upside down in death.

This collecting reminds me of Percy Shelley's funeral pyre on the shores of where he drowned. His heart ( possibly due to calcification from tuberculosis ) resisted burning and was snatched from the flames. Mary Shelley kept it wrapped in his poem 'Adonais' within her desk until 1889 when it was buried in the family vault.

There are connections here, a constellation of grief.

On Shelley's gravestone:

lines from Ariel’s Song, via Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”:

“Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.”

* via Hayden Herrera